Addressing the Speech Needs of Children Learning English

In Ivan Campos’ work in California schools, the speech language pathologist (SLP) sometimes sees students from Guatemala who communicate in three languages: they’re learning English, they speak some Spanish and at home with their parents they converse in the Mayan language Q’anjob’al.

As immigrant children who primarily speak other languages learn English, the differences in their language development can sometimes be mistaken for language disorders.

“Bilingualism or multilingualism – it’s not the same for each child,” said Campos, a bilingual SLP in California’s Riverside Unified School District. “It’s very different than monolingual language development, and even early stages of second-language learning can appear to be language impairment.”

It’s a common problem among school-aged children who are exposed to a new language for the first time. English proficiency exams do not always account for students’ cultural backgrounds or gaps between their social and academic language abilities. But there are strategies parents and caregivers can take to advocate for their children’s speech and language needs.

Where Do Multilingual SLPs Work?

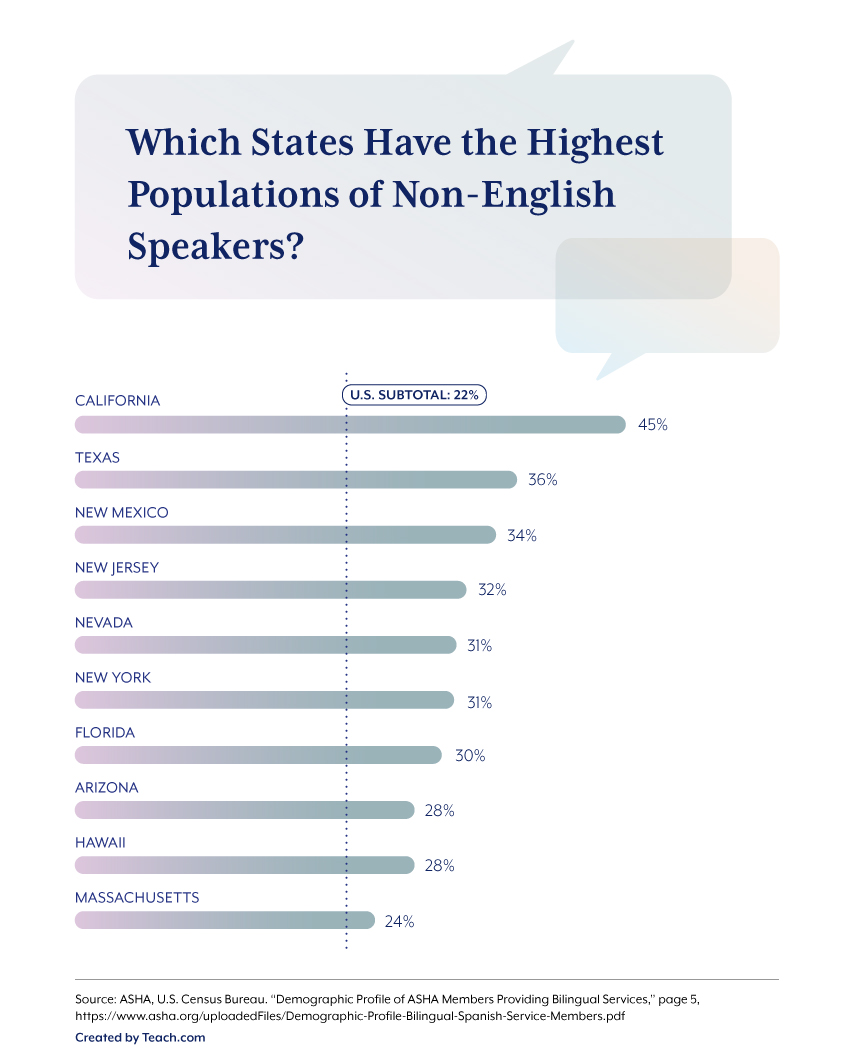

More than a fifth of the U.S. population spoke a language other than English at home (PDF, 455 KB) in 2018, and 8.5% of people reported speaking English less than “very well,” according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Communities Survey. Populations that primarily spoke a language other than English at home were highest in California, Texas, New Mexico, New Jersey, New York and Nevada. And California, Texas, New York, New Jersey, Florida, Hawaii and Nevada also had the highest concentrations of people who spoke English less than “very well.”

Percentages of individuals who spoke a language other than English as their primary language at home in 2018 were highest in California (45%); Texas (36%); New Mexico (34%); New Jersey (32%); New York; Nevada (31% each); New York (31%); Florida (30%); Arizona (28%); Hawaii (28%) and Massachusetts (24%).

Source: ASHA, U.S. Census Bureau. “Demographic Profile of ASHA Members Providing Bilingual Services,” page 5, https://www.asha.org/uploadedFiles/Demographic-Profile-Bilingual-Spanish-Service-Members.pdf

Overall, only 6% of all SLPs and audiologists registered with the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) were bilingual in 2018, according to the association. Of those providers, 64% were Spanish-language providers.

Although bilingual speech pathologists are rare, many are concentrated in states with the highest needs. New Mexico had the highest percentage of bilingual SLPs at 14.2%. And in Texas, Florida, California, Washington, D.C., and New York, at least 10% of SLPs were bilingual.

Like most SLPs, the majority of bilingual SLPs work in educational or health care settings (49% and 43%, respectively), and about a third are in private practice.

Why Are Speech Disorders Misdiagnosed in English-Language Learners?

English-language learners (ELLs) can often be misdiagnosed with language disorders as they are learning a new language when they are instead expressing language differences.

There are several reasons English-learning students are diagnosed (or misdiagnosed) with language disorders, said Campos, who speaks both English and Spanish. In some cases, students are not receiving adequate academic support and instruction when they require extra support to help them thrive. Issues outside the classroom, such as unstable housing or deportation of a parent, can also negatively influence a student’s academic performance. Other students have actual learning disabilities.

If a bilingual child has speech or language problems, those issues will appear in both languages. But learning another language does not cause or worsen speech or language problems, according to an ASHA article on the advantages of being bilingual.

“When speech pathologists come across English-language-learner students who actually have language impairments, they may struggle with them because the student has difficulty learning a language due to a learning profile versus a typically developing English language learner,” Campos said.

Over- and under-identification of language disorders is common, meaning schools may end up investing resources in speech therapy treatments for students who don’t need them or hindering the success of students who truly need speech therapy services but do not receive that support.

Some students may not receive the assessments they need if their schools do not prioritize speech-language assessments that are tailored to individual English language learners (ELLs).

“School-based SLPs may feel overwhelmed with their high workloads and caseloads and may also need additional training to conduct a culturally responsive assessment of their student with access to interpreters,” Campos said.

What Challenges Do English Language Learners Face?

Many standardized tests to assess English proficiency are designed based on monolingual speakers or irrelevant cultural contexts. Language assessments that are created based on speakers from one country are often applied to students from a variety of countries and cultures, which may have different communication customs. The gap between students’ social language skills and academic language skills can also cause professionals to falsely assume children have language-learning disabilities.

Every state sets its own assessment standards for English language learners in schools, and teachers are required to provide support for students based on their scores. Those supports can include measures like adding supplemental instruction, connecting new lessons with old concepts, providing preferred seating and including repetition. But as Campos explained, standardized tests don’t always show the full picture of students’ language capabilities.

“We have a field that is over-reliant on standardized scores. They want the number. And when you use an informal measure, it’s all your clinical judgment,” he said. “This is why we have so many kids who are English learners in special ed, and they maybe don’t belong there because of what tools we use to assess their language skills.”

Furthermore, assessments are not always normed on students’ peers with similar cultural backgrounds.

“You need to compare this student to other students of similar backgrounds in terms of language acquisition, history, culture, number of years of instruction—all of those factors—in order to compare them against same-aged peers,” Campos said.

For example, it’s unfair to compare a third grader who arrived from Guatemala in kindergarten to a third-grader who’s lived in the United States his whole life and whose family only speaks English.

“That happens all the time,” Campos said. “Teachers don’t always wait. This is going to be a process to learn another language.”

Glossary of Language Acquisition Terms

Basic Interpersonal Communication Skills (BICS): Social language proficiency, which typically takes two to three years to develop.

Codeswitching: Switching fluidly between multiple languages when engaging with other multilingual individuals.

Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency (CALP): Advanced language proficiency, which can take five to 10 years to develop.

Dominant language: The language a child knows better, which can change over time.

Fossilization: Using elements of one’s primary language, such as sound substitutions, in a learned language.

Heritage speakers: People who understand their first language but no longer express it. They can appear to have language loss.

Interference/transfer: Using structural elements of the first language in the second, such as mixing grammar rules, which can cause errors in the language being acquired.

Language loss: Losing skills and fluency in one’s first language while learning a second language.

Sequential language acquisition: Learning one language and then another.

Silent period: A time during which language learners focus on listening and comprehension when they are first exposed to a new language. Sometimes students going through a silent period are diagnosed with selective mutism.

Simultaneous language acquisition: Learning two (or more) languages at the same time since birth.

Tips for Seeking Speech-Language Services for Bilingual Children

Challenge: Cultural and linguistic barriers

Some parents of immigrant children are also English language learners. In addition to learning a new language, they may come from cultures where language is used differently or where authority is viewed differently.

TIP: GET INVOLVED WITH PARENT GROUPS THAT INCLUDE OTHER PARENTS WHO ARE ALSO SECOND-LANGUAGE LEARNERS TO COLLECTIVELY ADVOCATE FOR STUDENTS’ NEEDS.

Challenge: Access to services

Multilingual SLPs are rare. It can sometimes be difficult for parents and caregivers to find SLPs who speak their language or their child’s primary language—especially if their primary language is not Spanish.

TIP: WORK WITH AN INTERPRETER ALONGSIDE AN SLP. SCHOOL SYSTEMS SHOULD PROVIDE INTERPRETERS TO TRANSLATE FOR CHILDREN WHILE SLPS CAN MAKE ASSESSMENTS ABOUT THE CHILD’S SPEECH AND LANGUAGE SKILLS.

Challenge: Language barriers between caregivers and children

Some foster parents may speak a different language than the child in their care.

TIP: WORKING WITH AN INTERPRETER CAN ALSO BE HELPFUL FOR CAREGIVERS WHO SPEAK A DIFFERENT LANGUAGE THAN THEIR CHILD.

How SLPs and Educators Can Help Students Learning English

EMPOWER PARENTS AND CAREGIVERS TO ADVOCATE FOR THEIR CHILDREN.

Parents of non-English-speaking children may have their own barriers in advocating for their children, such as illiteracy, limited schooling or feelings of intimidation by American school systems and authorities.

“Parents are experts too, but how many parents give themselves that credit?” Campos said.

Professionals can help ease those challenges by partnering with groups for parents learning English as a second language (ESL) and by connecting parents to those types of support systems.

ENSURE PARENTS AND CAREGIVERS UNDERSTAND THE TREATMENT FOR THEIR CHILD.

Parents may not speak the same primary language as their child, or they may not have strong language skills themselves.

“School teams need to amend their language to the parents’ level,” Campos said. “Not to disrespect a parent but to make sure that you’re using terms that the parent understands.”

CONSIDER LINGUISTIC AND CULTURAL CONTEXTS WHEN ASSESSING CHILDREN.

Assess a student’s language abilities using clinical judgment and by observing their capabilities in all languages they speak. Don’t entirely rely on standardized testing; use informal measures to assess a child’s capabilities, too.

APPROACH STUDENTS WITH “CULTURAL HUMILITY.”

Professionals should recognize the setbacks faced by the immigrant children they serve who do not speak English and should advocate systematically for them in an attempt to level power imbalances, Campos said.

“You also recognize how your own ethnocentric prism can impact how you view other students,” he said. “So, you’re checking yourself along the way through your biases, but you’re also willing to learn and actually be proven wrong about certain situations.”

SEE STUDENTS FROM OTHER BACKGROUNDS AS CONTRIBUTORS TO THE CLASSROOM.

Rather than viewing English language learners as being at a disadvantage, find ways to incorporate their language and culture as they are learning English.

“Let’s change the language and say, ‘Oh, you’re bringing all this culture, you’re bringing all this language to the table. Let’s find ways to connect your language, your culture as we’re learning English,’” Campos said. “So, there are two thoughts: There is the child who shows up as a deficit or the child who shows up as a contributor with all these things.”

Additional Resources for English Language Learners

These resources can help parents, caregivers and educators find the support they need for children learning English.

- ASHA: Acquiring English as a Second Language

- ASHA: Learning Two Languages

- ASHA: Working with Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CLD) Students in Schools

- Bilinguistics: Speech Therapy Materials

- Bilingual Therapies: Bilingual Speech Pathologist Resources

- Colorín Colorado!

- Difference vs. Disorder: Speech Development in Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Populations

- Reading Rockets: English Language Learners