Teaching Strategies and Classroom Policies to Help Students With Anxiety Disorders

Anxiety is a common mental illness that affects not only adults but also children. According to data on children’s mental health from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), roughly 5.8 million children in America struggle with diagnosed anxiety. And, for students, anxiety disorders don’t only show up as feelings or nervousness on the first day of school; anxiety can also hinder a child’s self-esteem, academic performance and overall well-being.

“It’s just a fact of life that there will be children who struggle with anxiety and other mental health issues at school,” said Kathariya Mokrue, a clinical psychologist and associate professor of psychology at York College. “If educators know that going in, they can put into place policies to address and support these children so that they can be successful in their lives academically and beyond.”

As role models who spend most of their day with their students, educators play a critical role in children’s development. Through the lens of compassion, educators can harness specific teaching strategies and classroom policies that can better assist those struggling with anxiety.

What Does Anxiety Look Like for Kids?

The American Psychological Association defines anxiety as an emotion characterized by tension, worried thoughts and physical changes such as increased blood pressure. According to the CDC’s data on children’s mental health:

9.4%

of children ages 3-17 have diagnosed anxiety

37.9%

of those children also had behavior problems

What Types of Anxieties Affect Children?

According to the Child Mind Institute (CMI), children can have a number of different anxiety disorders, including:

Separation anxiety: When children become very upset when separated from caregivers.

Social anxiety: When children experience anxiety due to peer and social interactions.

Selective mutism: When children struggle with speaking in certain settings, like at school.

Generalized anxiety: When children worry about lots of things, including academics.

According to a fact sheet by KidsHealth, anxious children might worry about things as small as recess, birthday parties and school bus rides, or bigger issues such as war, illness and loved ones. It can make it hard for them to focus in school because they are constantly worrying.

Anxiety manifests differently in children, said Mokrue, who is also a professional member of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America and sits on the ADAA public education committee. Some children may seem withdrawn, internalizing their anxiety. Others might act out or misbehave. While it may not always be obvious how a child is experiencing anxiety, there are some cues depending on age.

Younger children tend to struggle more with separation anxiety.

Being separated from a parent or caregiver can be difficult for a younger child who is beginning preschool or new to having playdates. They may have a hard time being apart from their parents or caregivers even for a short while. They may also avoid certain situations where they don’t want to be without their parents or caregivers. Children with phones may be more likely to constantly text their parents or caregivers throughout the day, CMI reports.

Mokrue said this is because younger kids are often unable to articulate their feelings. Instead, they may cry or look upset if they are feeling uncomfortable and anxious.

Older children tend to struggle more with social and academic anxiety.

When children get older, they start to become more preoccupied with earning peer acceptance and may develop social anxiety. Social anxiety can manifest in avoidance of certain situations where children are expected to perform socially, such as going to school, eating in public or even having conversations with others.

Some children might feel anxious about doing well in school, so they are more likely to be extra concerned about following directions correctly and often ask for reassurance from educators. Others may struggle with focusing and feeling too distracted to pay attention in the classroom. There are also students who fear speaking up in class because they’re afraid to be wrong.

How Do Children Respond to Anxiety?

“Anxiety is about uncertainty. So it’s feeling out of control with what will happen next and being incapable of handling the challenge,” Mokrue said.

Triggers such as an unexpected quiz or test can increase anxiety in children, she explained. The disruption to consistency is what acts as the trigger for the student.

The students can respond to these triggers in various ways to alleviate their anxiety. CMI reported they may take frequent trips to the nurse, avoid group work, fail to turn in homework, miss school and have difficulty answering questions in class.

Anxiety can create physical symptoms, such as shakiness, clammy hands or a racing heart. According to KidsHealth, these symptoms happen because of an overactive “fight or flight” response, which can happen even if there is no real danger present.

Anxiety can impact a child’s education in the sense that they may struggle to focus or worry too much about how they’re doing to pay attention in the classroom. They may not tune into what the teachers are saying or pick up on cues from friends.

Consequently, the student might miss important material, which exacerbates the problem and creates more anxiety. Students may also begin to feel socially anxious if their peers are talking about their performance in the classroom, creating a feedback loop where students feel helpless.

6 Ways to Help Students With Anxiety

1

Start with the culture of the school.

Mokrue encourages schools and educators to create a culture of kindness and destigmatization that can help support students who are struggling with anxiety.

“If schools can accept that mental health is an important aspect that impacts the lives of children as well as adults, then they can take a more proactive rather than reactive approach when anxiety-related problems do come up,” she said.

2

Teach how to identify emotions.

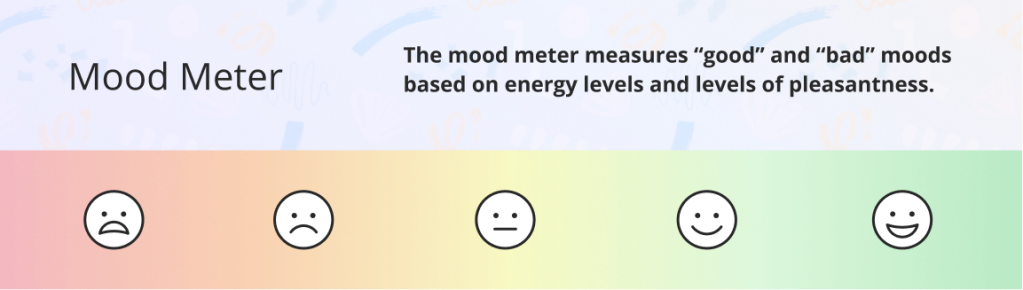

Educators can have regular check-ins with their students by using a mood meter. This may be more appropriate for younger children who are still developing their language around feelings beyond sadness, anger or joy. Mood meters can help children verbalize a wide range of emotions, including boredom and calmness.

The mood meter has a red zone for feeling bad, and a green zone for doing OK. These can be cues for the educator to set aside time for the child and discuss what to do next. The red zone can indicate a child may need to step away from the environment to calm down and reassess. Children can also write a statement about how they feel and share it with the educator, who can then help them work on verbalizing what they are feeling more clearly.

3

Collaborate with parents and caregivers.

Encourage discussions around social emotional learning both at home and at school, Mokrue said. Educators can also work with parents to find common ways to support children in both settings. This could be done by finding the source of the anxiety, identifying what learning and behavioral needs a student has, setting goals and implementing strategies for managing anxiety at home and at school, and monitoring the student’s progress over time.

If a student is missing class often for some reason, educators can make sure to always check in with parents ahead of time to help the student prepare to return to school.

4

Consider what classroom policies and practices can be adjusted.

Educators should think through what might be causing anxiety and determine if there are simple, nondisruptive changes to how they interact with students that may alleviate their stress. Some examples might include:

- Allowing students to present to educators alone or do a short presentation in front of a smaller group of students if they have anxiety about public speaking.

- Allowing students to move their desk away from the front of the classroom or switching seats regularly if they struggle with being in the spotlight.

- Allowing students who struggle with distraction to choose seats closer to the front of the classroom to help them focus their attention.

- Providing directions in verbal and written form to ensure that those who are easily distracted don’t miss out on instruction.

- Providing advance notice about which students may be presenting, reading or solving problems to allow them to prepare.

- Encouraging students to make mistakes in pursuit of discovering answers and allowing them to work collaboratively to help each other rather than correct each other.

- Asking children at the beginning of the year if there are aspects of learning or the classroom that make them stressed.

Schools can also commit resources, such as school counselors, to conduct professional development, educate staff on mental health issues, and develop partnerships with mental health experts to be more proactive addressing student anxiety, said Mokrue.

5

Create opportunities for students to temporarily escape their anxiety.

For children, slowing down is essential both physically and emotionally to help regulate anxiety. Practicing mindfulness can help anchor their attention on something neutral and redirect focus whenever distractions, such as a bad thought, happen.

According to Mokrue, taking time out of the day to be present and shift thoughts away from anxiety can help promote better focus and cognitive control, which can help with emotional self-regulation. This can look like short yoga breaks or daily walks between classes.

6

Offer encouragement and model resilience.

Educators can help students feel less anxious by providing positive reinforcement that isn’t consumed with outcomes. Noting small efforts and highlighting how students embrace challenges are good ways to boost morale.

Educators can also model important behaviors. For example, when children see their teacher make a mistake and recover from it, teachers are modeling skills that help students reframe how they think about obstacles or missteps. This can help children regulate their emotions, which in turn helps them perform better.

“It’s important to take care of the whole child, not just the academic piece. It’s about keeping them not only physically safe, but also mentally and emotionally safe,” Mokrue said.

The following article is for informational purposes only. Adults who would like to support a child with an anxiety disorder should consult a mental health practitioner or licensed specialist.